12 Review of calculus*

Calculus is a prerequisite to work with continuous distributions. The following chapters assume readers are proficient in calculus. We nonetheless review some basic concepts here as a warm-up. This review is not exhaustive, so please refer to a specific textbook if needed for a more comprehensive understanding.

Differentiation

We define the derivative of a function \(f(x)\) to be \[f'(x)=\lim_{h\to0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\]

Loosely speaking, a function is continuous if there is no jump in the graph, differentiable if the curve is smooth. Some commonly used derivatives:

\[\begin{aligned} & \frac{d}{dx}(x^{n}) & = & nx^{n-1}\\ & \frac{d}{dx}(e^{x}) & = & e^{x}\\ & \frac{d}{dx}(\ln(x)) & = & \frac{1}{x}\\ & \frac{d}{dx}(\sin(x)) & = & \cos(x)\\ & \frac{d}{dx}(\cos(x)) & = & -\sin(x)\\ & (fg)' & = & f'g+fg'\\ & \left(\frac{f}{g}\right)^{'} & = & \frac{f'g-fg'}{g^{2}}\\ & [f(g(x))]' & = & f'(g(x))g'(x) \end{aligned}\]

When dealing with limits of the form “\(\frac{0}{0}\)” or “\(\frac{\infty}{\infty}\)”, the L’Hospital rule is very handy. \[\lim_{x\to a}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\lim_{x\to a}\frac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}.\]

One important application of derivatives is the Taylor’s theorem, which gives the approximation of a function around a given point by polynomials. Assume function \(f\) is at least \(k\) times differentiable, then

\[f(x)=f(a)+f'(a)(x-a)+\frac{f''(a)}{2!}(x-a)^{2}+\cdots+\frac{f^{(k)}(a)}{k!}(x-a)^{k}+\cdots\]

which means we can approximate a function arbitrarily well by higher order polynomials. Some commonly used Taylor series (expanding around \(a=0\)):

\[\begin{aligned} & \frac{1}{1-x} & = & 1+x+x^{2}+x^{3}+\cdots\quad\textrm{for }|x|<1\\ & e^{x} & = & 1+x+\frac{x^{2}}{2!}+\frac{x^{3}}{3!}+\cdots\\ & \sin x & = & x-\frac{x^{3}}{3!}+\frac{x^{5}}{5!}-\frac{x^{7}}{7!}+\cdots\\ & \cos x & = & 1-\frac{x^{2}}{2!}+\frac{x^{4}}{4!}-\frac{x^{6}}{6!}+\cdots\\ & \ln(1+x) & = & x-\frac{x^{2}}{2}+\frac{x^{3}}{3}-\frac{x^{4}}{4}+\cdots\quad\textrm{for }|x|<1\\ & \arctan(x) & = & x-\frac{x^{3}}{3}+\frac{x^{5}}{5}-\frac{x^{7}}{7}+\cdots\quad\textrm{for }|x|\leq1 \end{aligned}\]

Taylor series are one of the most amazing results in calculus. For example, in the last formula, if we let \(x=1\): \[\frac{\pi}{4}=\arctan(1)=1-\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{5}-\frac{1}{7}+\cdots\] Therefore, we can approximate \(\pi\) by summing up a sequence of fractions: \[\pi=4\left(1-\frac{1}{3}+\frac{1}{5}-\frac{1}{7}+\cdots\right).\]

Integration

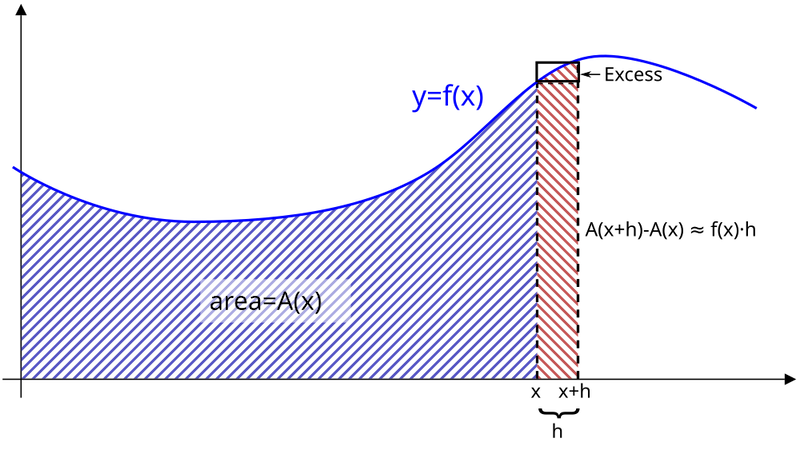

Integration is the inverse operation of differentiation. Integral has the geometric interpretation as the area under the curve. Let \(A(x)\) be the area under the curve of \(y=f(x)\). Thus \(A(x)=\int_{0}^{x}f(t)dt\). The change of the area resulted from a tiny little change of \(x\) is approximated by \(A(x+h)-A(x)\approx f(x)h\). That is \(\frac{A(x+h)-A(x)}{h}=f(x)\). If the change is infinitesimal, \(h\to0\), we have \(A'(x)=f(x)\).

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: if \(F\) is the anti-derivative of \(f\), then

\[F(x)=\int_{a}^{x}f(t)dt\] \[\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx=F(b)-F(a)\]

One interpretation of the integral is — the integral of a rate of change of a quantity gives the net change in that quantity. Think about speed and distance: \(\int_{a}^{b}v(t)dt=s(b)-s(a)\).

Because the integral is just a sum over infinitely many approximating rectangles, \(\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx=\lim_{n\to\infty}\sum_{i=1}^{n}f(x_{i})\Delta x\). Integrals behave just like sums. For example, \(\frac{1}{b-a}\int_{a}^{b}f(x)dx\) has the interpretation of the average of \(f(x)\) from \(a\) to \(b\).

Indefinite integrals are the general antiderivatives without specifying the interval of the integration. It always comes with a constant \(C\). Some commonly used integrals:

\[\begin{aligned} & \int dx & = & x+C\\ & \int x^{n}dx & = & \frac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}+C\\ & \int e^{x}dx & = & e^{x}+C\\ & \int\frac{1}{x}dx & = & \ln|x|+C\\ & \int\cos(x)dx & = & \sin(x)+C\\ & \int\sin(x)dx & = & -\cos(x)+C\\ & \int\frac{1}{1+x^{2}}dx & = & \arctan(x)+C \end{aligned}\]

Two common integration techniques are substitution and integration by parts.

Example 12.1 (Integration by substitution) Find \(\int\sqrt{3x+2}dx\).

Solution. Let \(u=3x+2\), then \(du=3dx\). Then \[\int\sqrt{3x+2}dx=\frac{1}{3}\int\sqrt{u}du=\frac{2}{9}u^{3/2}+C=\frac{2}{9}(3x+2)^{3/2}+C.\]

Example 12.2 (Integration by parts) Find \(\int x\sin xdx\).

Solution. Integration by parts follows the formula: \[\int f(x)g'(x)dx=f(x)g(x)-\int f'(x)g(x)dx\] Let \(f(x)=x\), \(g'(x)=\sin x\). Then \(g(x)=-\cos x\). Then, \[\int x\sin xdx=-x\cos x-\int(-\cos x)dx=-x\cos x+\sin x+C.\]